What is SRE and why should you love it?

-

4505

-

4

-

0

-

0

SRE is the acronym for Service Reliability Engineering, a term that was coined by Google experts back in the early 2000-s. It predates the DevOps methodology introduction by nearly a decade and is nearly as old as Agile manifesto. However, SRE does not contradict DevOps — in fact, they form an excellent working relationship, complementing and supporting each other.

Many self-appointed “experts” will proclaim that SRE is centered on “you built it, you run it” motto coined by Amazon CTO Dr. Werner Vogels. This means, according to these so-called “gurus” that developers must learn to run the systems in production, so they get a better understanding of how to write the code to ensure it works well after the release.

This is utter nonsense and cannot be farther from the truth. Ben Treynor, the Head of the Google Service Reliability Engineering team, who coined the SRE term itself, has clearly outlined what SRE should be and how it should be used. According to him, “SRE is what happens when the software developer must handle operations” ©. This is where most of the “experts” stop, so they end up with completely wrong assumptions on what was actually said here.

What is SRE in simple words?

Actually, if one reads the “SRE: How Google runs production systems” book, it becomes self-explanatory, that the meaning of the phrase is quite different. The service reliability engineer must work on ensuring … service reliability, by treating the wholeness of the applications and systems in production as an application, and managing it in a way to ensure optimal performance. Therefore, SRE specialists must have experience both with cloud infrastructure management and software development — but they must concentrate more on the Dev side of things, while DevOps concentrates more on the Ops side of operations.

How does it differ from classic software development? Not so long ago, the Dev and the Ops team were different (and quite often opposing) camps. While the efficiency of the Dev team was measured by the number of features they successfully delivered, the efficiency of the Ops team was measured based on the application uptime — and new feature releases quite often have lead to service downtime.

Thus said, the goals of these two teams directly contradicted each other, and they had separate silos of tasks, tools and skills. The common approach to handling the code was “throw it over the wall to be someone else’s trouble”, which has lead to constant tension and pulling the blanket between the two departments in almost any company. Most importantly, this resulted in an unpredictable software delivery schedule, immense customer frustration and financial losses due to post-release downtime and the fear of innovating due to the risk of bearing the blame for failure.

What is DevOps then?

The daunting situation described above required drastic measures, so the DevOps approach was introduced. Much as with SRE, many “experts” assumed that to enable DevOps you should make Devs and Ops sit in one room and teach each other to code and to run infrastructure, so they share their skills, tools and tasks. This way, the “gurus” assume, the DevOps magic will happen and the teams will become fully interchangeable.

In fact, such an approach would be a direct way to a disaster, as both teams would lose productivity. To say more, each of the specialists you employ has studied their chosen field for years to reach their professional level, and it would take years for them to teach their colleagues everything they know (and to learn from them) in order to form an interchangeable team.

DevOps is NOT and NEVER HAS BEEN a mix of Dev and Ops. It IS a paradigm centered at communication and collaboration between the teams, where OPS engineers are at the head of the table, as they deal with the application 90% of the time, while it runs in production. So OPS engineers define how to structure the future application best (monolith or microservices), how to ensure timely and error-proof application updates (through automated testing and CI/CD pipelines) and how to manage and monitor the production cost-efficiently (through smart alerting and predictive analytics, instead of manual system monitoring).

The DEV part of the DevOps relates to the fact that when the Dev and Ops teams have met and discussed the structure of the future app, the Ops create AUTOMATED TOOLS to support Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery of new code — Terraform and Kubernetes manifests that Devs can run with ease, without having to dive deep into the infrastructure management part of things. This way, the Devs can create code without wasting time on requesting the Ops engineers to build and configure testing environments for it, or preparing the releases. Once the manifests are in place, the development becomes much more predictable.

Thus said, the DevOps culture fosters collaboration between the teams and individuals, as their goals are now aligned — they have to ensure the application runs reliably at all times while being incrementally improved without interrupting the end-user experience. They retain their skillsets and tools — they just communicate freely with each other to understand how to help each other work as productively as possible — without distracting each other with repetitive routine requests.

Most importantly, DevOps culture treats failure not as a sign of incompetence, but as an indicator that there is some room for improvement in your product, infrastructure or workflows. It is also important that IaC, CI and CD principles of DevOps help create and configure the required testing environments literally in seconds, so the cost of error after failing and experiment is close to zero. This blameless postmortem approach removes the tension and helps all parties be more innovative in their experiments — which helps deliver great new features and products faster.

Enter SRE — when Devs have the final say

What is the difference between DevOps and SRE then, and why would you need SRE at all, if DevOps is so good? Because SRE specialists can help improve both your applications and infrastructure as a whole, which is essential when operating infrastructures at scale. Most importantly, SRE does not contradict DevOps and is actually an important part of it.

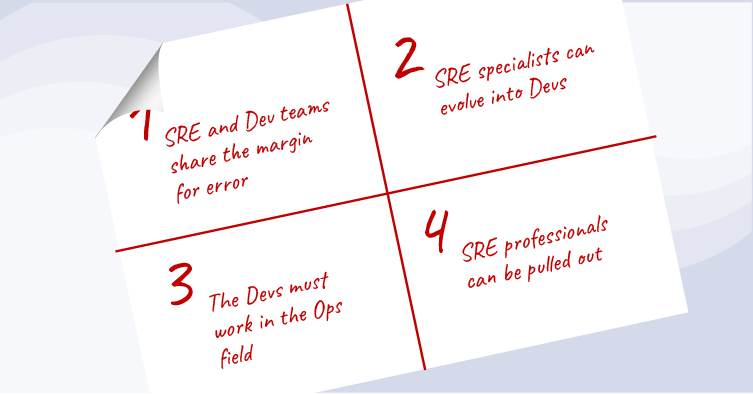

How to obtain such experience then? Ben Treynor described 4 basic rules of SRE:

- SRE and Dev teams share the margin for error. They sign an internal SLA agreement, where they define the minimal monthly service uptime — let’s say it is 99,95%. This means that the Devs can make mistakes that lead to service downtime 0,05% of the time. Once this quota is used up, no new deployments can take place until the end of the month.

This approach serves two goals at once: the Devs are not afraid to experiment, as they know they have some room for mistakes. They are also very cautious as not to exceed this limit and ensure they do have capability to deploy new features. Therefore, instead of building product features in long branches with multiple merge conflicts before the release, the developers write code in small batches that are easy to test and integrate with the main product — the CI principle of DevOps. - SRE specialists can evolve into Devs. SRE and Dev teams share the recruitment quota. This way, if the Dev team needs 1 more man to deliver new product features, the SRE team can hire 1 less man to handle it in production. This incentivizes the Devs to write a cleaner, better-performing code that can be handled by fewer SREs, so they can gain more Dev headcount and deliver new, better features faster.

To ensure this, SRE teams are composed of top-notch sysadmins with a good working understanding of code development. They can both run the systems and the applications — and fix the bugs in the code. Most importantly, SRE’s must spend at least 50% of their time refactoring and improving the code they run, and they can upgrade to Developers once the system can be handled by fewer SRE specialists. This way, many of Google’s SRE talents have evolved into full-stack Devs and became engaged with building new exciting stuff, instead of simply running it. - The Devs must work in the Ops field. This is the principle described by Ben Treynor, which is often perceived incorrectly. The Devs at Google spend at least 5% of their time monthly serving as the first line of support. They deal with customer requests and help them sort out the challenges with their products – BUT THEY DON’T RUN THE SYSTEMS BENEATH.

They just get the firsthand experience of dealing with their products from the user perspective and are able to receive customer feedback and implement it quickly, drastically shortening the feedback loops. - SRE professionals can be pulled out. For example, SRE’s can move to another project or decide to pursue another line of professional growth. This is the prerequisite for keeping them motivated and productive. But if there is some tension between Devs and SREs, they can be split and all the SRE’s can be pulled out from the project, so the Devs have to keep the infrastructure running while also delivering new features. Over several decades of working at Google, Treynor had to promise this action just twice — and it sufficed to help both teams more productive and collaborative.

Conclusions: SREs are important for project success

To wrap it up — SRE approach helps system engineers learn to manage the infrastructure and application more efficiently, greatly increasing the reliability of operations and predictability of software development. It does not contradict DevOps and is actually one of 7 core DevOps roles. If you need SRE services or consulting on how to implement SRE in your organizations — IT Svit can help!